Jetx you are at the controls ready for takeoff

The Basics of the Cockpit Of a Plane

The cockpit of even the smallest and simplest airplane can be an overwhelming place. Fortunately, the most “hands-on” elements of the cockpit—those which enable the pilot to direct the airplane’s actual movement from taxiing to landing—are usually similar from one cockpit design to another.

Even if a new single-engine student pilot had never seen the astounding Boeing 777 cockpit, he or she could probably pick out its most basic control elements. But for the purposes of the next few hundred words, this article will focus on typical cockpit controls in smaller airplanes.

Knowledge about the controls of an aircraft goes hand in hand with a firm grasp of the forces of flight and how an airplane operates.

Becoming familiar with the major control surfaces of an aircraft will make it easier to command a cockpit. For example, a pilot will have a better understanding of how to efficiently operate an airplane’s rudders if he or she is confident in the knowledge of how a vertical stabilizer operates.

Ignition Control

When you start an automobile, you need a key or key fob to bring the engine to life. The same principle applies to small airplanes.

The “key” in this instance is the ignition control system. While a series of switches are used to rev up a small APU in the startup procedure of large commercial jets, pilots of a few smaller aircraft might demand an actual car-like key.

Older airplanes could require the operation of a lever during the ignition process, but most pilots work with automatic starters.

Most ignition switches have five positions: Off, right (R), left (L), both, and start. The “right,” “left,” and “both” refers to the magnetos, or electrical generators, within the airplane’s engines. Paying close attention to pre-flighting procedures can head off common problems in ignition control.

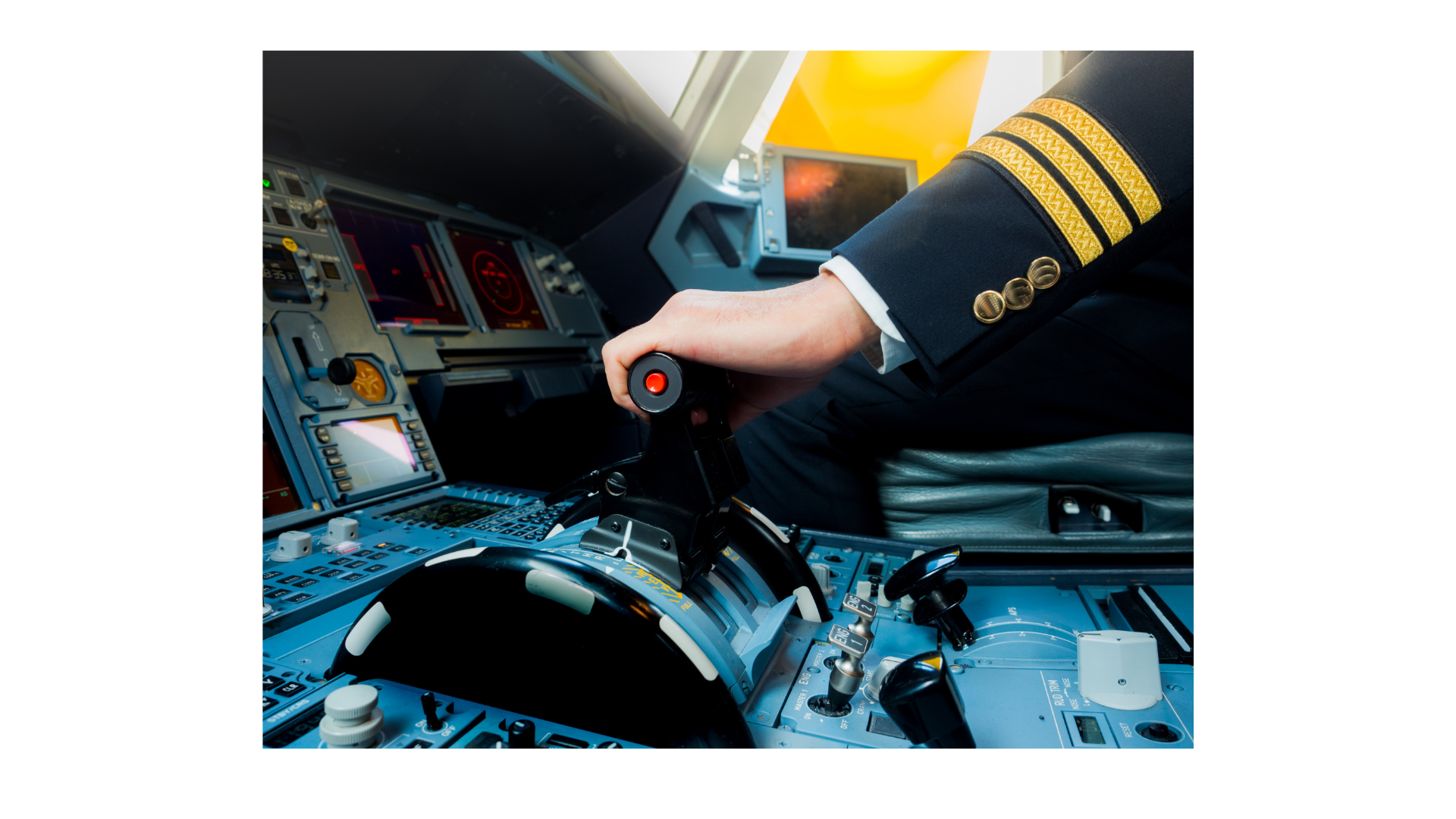

Yoke, Side Stick, Center Stick

When pilots are depicted in movies, they’re rarely shown making weight and balance calculations or dutifully filing flight plans. They’re usually in the thick of mid-flight action, yoke in hands.

The yoke is the airplane’s “steering wheel.” The yoke controls the airplane’s ailerons. In simplest terms, it allows the pilot to move the airplane “up,” “down,” “over left,” and “over right.”Twisting the yoke side to side controls roll and pitch. Pushing forward on the yoke directs the nose of the airplane toward the ground; pulling back on it commands the nose to pull up.

Yokes are seen on fixed-wing airplanes, and are also known as the “control wheel.” Conventional yokes are shaped like either a W or a U, with a few available as a M or “ram’s horn.”Smaller aircraft’s yokes are attached directly to the instrument panel with a sturdy tube.

Cirrus SR airplanes and some light sport aircraft are equipped with side sticks instead of yokes. This placement allows for a larger instrument display and is more lightweight than a traditional yoke. Some pilots prefer them over more traditional forms of control.

While some modern aerobatic airplanes and fighter jets use center sticks to more effectively work with G-forces, most pilots opening the door of an older airplane will see a stick instead of a yoke.

The control stick is usually located on the floor of the cockpit; the pilot straddles it in his or her seat. Sometimes called the “joystick,” it controls the airplane’s attitude and altitude like the yoke.

The Engine Control Quadrant: Throttle, Mixture, Propeller

Some airplanes offer pilots a single unit to operate the engine, with all the relevant controls grouped together in what’s called the engine control quadrant.

Other cockpits separate these controls, but they are usually grouped together, typically in the bottom center of the instrument panel.

The throttle is the airplane’s engine power control. It’s similar to a gas pedal in a car. Usually colored black, the throttle is either a push-pull device or a lever. By adjusting the amount of the fuel/air mixture via the throttle, the pilot is adding or subtracting power to the airplane’s engine or engines.

On airplanes with controllable (or variable) pitch, pilots will find the propeller control next to the throttle. This operates the propeller RPM, allowing the pilot to call for more power during takeoff, then adjust for fuel efficiency while in flight. It’s typically colored blue.

Next to the propeller control is a mixture, which is red. This deals with the ratio of fuel to air which enters the engine. When the airplane is taking off, the pilot sets the mixture to “rich” to allow for the maximum amount of fuel. During cruise flight and landing, the mixture knob is adjusted to more “lean,” or efficiently allow more air.

Flap Handle

If a small airplane was produced from the late 1970s on, pilots will usually find a flap control switch on the instrument panel. It’s traditionally white and horizontal to the cockpit, and sometimes it’s even shaped like a small flap. Typically placed next to the throttle, the flap handle allows the plot to increase lift as well as drag. The flap handle is mostly used during takeoff, approach, and landing.

In airplanes built prior to the 70s, if a pilot wants to control an airplane’s flaps, he or she uses a handle located near the seat. Pulling up on it lowers the flaps.

Rudder Pedals

As if there’s not enough to be concerned with on the instrument panel, the pilot must also become familiar with the rudder pedals on the floor of an airplane. But be glad those pedals are there—the first airplanes had no brakes at all, and pilots simply slowed down and trusted that a bumpy grass runway would roll the airplane to a stop.

The rudder controls the yaw or the direction of the airplane to the “left” and “right.” The pedals control the trailing edge of the airplane’s vertical stabilizer. In most small airplanes, rudder pedals also control the wheel brakes when the pilot pushes on the top part of the pedals.

Ready to soar in your aviation career?

Schedule a Meeting Here

Mr. Matthew A. Johnston has over 23 years of experience serving various roles in education and is currently serving as the President of California Aeronautical University. He maintains memberships and is a supporting participant with several aviation promoting and advocacy associations including University Aviation Association (UAA), Regional Airline Association (RAA), AOPA, NBAA, and EAA with the Young Eagles program. He is proud of his collaboration with airlines, aviation businesses and individual aviation professionals who are working with him to develop California Aeronautical University as a leader in educating aviation professionals.